Building Communities and Diplomatic Success

In this newsletter:

1. Interfaith, Building Community. Compassion in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam

2. Elijah Mourns the Passing Away of Rabbi Shear Yashuv Cohen

3. Judaism and Eastern Religions – Diplomatic Success and Theological Challenges

4. Sharing Wisdom

===========================================

1. Interfaith, Building Community. Compassion in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam

Contributed by Rozemarijn Vanwijnsberghe, I.T.OUCH’

Elijah Interfaith Institute participated in a summer school program on “Interfaith, building community” for youth leaders organized by I.T.OUCH. It was a moment of special gratification for Elijah staff, inasmuch as the entire seminar was in some way a fruit of the summer school on Religious Genius, that took place in Israel last year. One of Elijah’s students runs I.T.Touch, an interfaith organization growing out of the Teresian Association based in Brussels, with broad European reach, and incorporated Elijah’s methodology and its emphasis on Religious Genius in the curriculum of the summer school. The summer school took place in Perugia, Italy from August 17-24.

An intergenerational and multilingual group from Belgium, Korea, France, the Philippines, Hungary, Italy, the Holy Land gathered together for this one week intensive and interactive learning experience. The group brought together an agnostic, a Buddhist, Jews, Christians (Catholics and Protestants) and Muslims (Sunnis and Sufis). The participants reflected on three religious traditions, guided by three experts: Truus Schouten, Dutch Protestant pastor and biblical scholar, Laura Martín, expert on Spiritual Islam (Sufism) and Alon Goshen-Gottstein of The Elijah Interfaith Institute.

The group made a “pilgrimage of compassion and peace”: There was a meeting with the imam of the Islamic Center of Perugia and his wife, founder of the European Forum of Muslim women, EFOMW. They visited Assisi and the monastery of Saint Masseo where they prayed vespers with the monks of the Benedictine ecumenical community of Enzo Bianchi, Monastero di Bose. They discovered the Jewish community of Siena, (see Sinagoga de Siena) and, after speaking with the auxiliary bishop of Perugia on the experience, they attended the celebration of Sunday Mass in the chapel of the university residence.

Alon Goshen-Gottstein introduced the concept of “religious genius” and guided the reading of various texts of each of the traditions under study: Gregory of Nazianzus, al-Ghazālī, and Rav Kook.

With “InTerfaith, building community,” I.T.OUCH and partner organizations hope to have started a dynamic generator of life for today’s world. They concluded by expressing a wish: “We hope to have more of these realities. We do not stop dreaming ….”

—————

2. Elijah Mourns the Passing Away of Rabbi Shear Yashuv Cohen

Elijah mourns the passing away of Chief Rabbi Shear Yashuv Cohen, a founding member of the Elijah Board of World Religious Leaders.

Rabbi Alon Goshen-Gottstein posted the following to his blog, in loving memory of Rabbi Cohen.

Rabbi of Love and Harmony: Personal Recollections of Rabbi Shear Yashuv Cohen

I knew Rabbi Shear Yashuv Cohen for most of my life, certainly for more than 50 years. He lived up the road; he was part of the humanscape of my childhood. As a young adult I began appreciating his open-mindedness. He was there in times of crisis, typically crises created by my own lack of discrimination in terms of what to say to whom, and when.

Here is an anecdote. When, in my early twenties, I did a course of military chaplains, I felt free to express my opinions regarding internal Jewish pluralism. the Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox religious establishment that governed military chaplaincy was a matter of a closed club, and there was no room for any recognition of internal Jewish pluralism. To voice the opinion that Reform Judaism was not all bad, that we must collaborate with it and that there is room for it in the greater Jewish world, was unheard of, a kind of betrayal of fundamental views that would make one’s loyalties and legitimacy suspect. And so, I found myself not graduating the course, suspect as a heretic.

The person who came to the rescue was Rabbi Shear Yashuv. I doubt he supported the views I expressed, but he had the capacity to tolerate difference, radiate love, and bring about harmony, regardless of views and positions.

And so, with his help the perfect rabbinic resolution was found: I would get my military rank from my military commander, not from the Rabbinate, as if he were qualified to rule on the legitimacy of my opinions as an Orthodox chaplain. As much as this little anecdote is telling about religious establishment, it is even more telling about the humanizing and relational approach of Rabbi Shear Yashuv Cohen, a priestly and princely man of peace, moderation, toleration and understanding.

A Jewish Leader among Other Faith Leaders

A Jewish Leader among Other Faith Leaders

I didn’t really come to appreciate the beauty of the man till we began working together, or maybe I should say — till he continued supporting me in my interfaith efforts. When I founded the Elijah Institute, 20 years ago, our students would go on trips to holy sites of the different religions. Haifa was a mainstay of our religious-educational touring and Rav Shear Yashuv a regular participant. Groups loved him. He was present. He cared. And his message was genuinely one of making room for all, regardless of religious difference.

He took pride in Elijah and in Haifa. Elijah was his first name, and this served for him as a link to our interreligious work. And Haifa was the ground in which a spirit of a tolerant Elijah was made manifest through his relationships with leaders of other faiths.

I believe there isn’t another chief rabbi, part of the Chief Rabbinate, who has taken as much care to cultivate relationships with clergy of other religions in his city. He participated in Iftars, fast-breaking on Ramadan. He maintained warm and jovial relations with Christian clergy. He famously quipped that he had a deal with Archbishop Elias Shakur of Haifa that when the messiah came, they would ask him if it was his first or second time around. The point is not the theological profundity of the exchange. It is the human warmth and depth of relationship that allowed him to cultivate relationships despite theological differences.

But it was more than personal warmth. It was common sense in practical and relational contexts.

I recall a telling moment that showed how unique he was in the landscape of the Israeli Rabbinate. The year was 2000. We are several months ahead of Pope John Paul II’s landmark pilgrimage to the Holy Land, the first one to take place with full recognition of Judaism and the State of Israel. A group of rabbis came to the Papal Nuncio’s residence to discuss how Shabbat violation might be kept to a minimum (how did I ever get to be part of that group? I think Rabbi Shear Yashuv invited me). The Pope was coming for the feast of the Annunciation, that was celebrated on Shabbat, and Jews would have to violate Shabbat to maintain law and order. What could be done to change the schedule?

It was a dignified meeting. Rabbi Shear Yashuv was a major voice. But that is not the most interesting part of the story. Guests were served drinks. Most were given water. On the wall above the sofa was an engraving of the historical encounter of Patriarch Athenagoras and Pope Paul VI, representing a high point of the ecumenical movement and rapprochement between different Christian factions. Water was served and Rabbi Shear Yashuv made the appropriate benediction out loud. No other rabbi drank. They signaled to each other, pointing to the decorative engraving. Rabbi Cohen looked in disbelief, unable to make out what all the fuss was about. The fuss was about fear, ignorance and the deep seated suspicion of images. These elements combined to create fear of something that had nothing of idolatry attached to it, as though it was a ritual object, leading to refusal to pronounce a benediction in that environment. Rabbi Shear Yashuv lacked that fear, distance and recoil. He had a natural demeanor that allowed him to be present, beyond differences. He also knew better and could distinguish ritual objects from works of art.

Rabbi Cohen and the Vatican

More or less at the same time, in the first years of the millennium, Rabbi Cohen found himself involved in two high-profile interreligious bodies. The one was the Chief Rabbinate’s permanent committee for dialogue with the Vatican. That the Chief Rabbinate chose him to head up the group is an expression of how clearly they recognized that he was suitable for the position. He was the best of the Chief Rabbinate for the task, and to this day his equal has not come forth. Over a 12-year period he headed up the rabbinical delegation, meeting with Vatican officials and seeking mutual understanding on a host of common concerns. In all this, theology was kept to the side. It was about facing the world together and it was founded on personal relationships.

Perhaps the summit of this part of his career was the invitation to address the Synod of Catholic Bishops in 2008, on the subject of the Bible and the Word of God. Rabbi Cohen was the first rabbi ever to address a synod. He referred to his presence there as “a signal of hope,” and “a message of love.” Even though he took a firm stand of opposition to the beatification of Pope Pius XII, his true message was one of love, because that is who he was. His love shone above and beyond stated differences.

A Partner in the Work of Elijah

At the same time, I issued Rabbi Cohen an invitation to join the Elijah Board of World Religious Leaders, a body that brings together top faith leaders of major faith traditions. He believed in the work. I suppose he trusted me. And he traveled far and wide in that capacity, recalling his membership in the Elijah Board whenever he spoke of his international activities. We were in Sevilla, Taiwan, Amritsar and other international destinations. He cared and he made the effort to be there not because the Rabbinate asked him to come, but because he believed in the work.

The Ultimacy of Love

I watched Rabbi Cohen through dozens of hours of small group and public conversations. I also spoke with him personally at great length. I was struck time and again by how classical his views were, and at the same time how open-hearted he was, as if there was little relationship between the views one held and who one was. He was ferocious when it came to Jewish rights on the Temple Mount, but his approach was characterized by the quest for harmony — he urged a synagogue along the mosque as a viable halachic, political and interreligious vision. It was a lone voice, but it expressed above all a spirit of inclusiveness within difference.

I noted how firmly he believed in the uniqueness of the Jewish soul, a clear extension and affirmation of the teachings of the school of Rabbi Kook, that he absorbed from birth, through his father, one of the premier disciples of Rabbi Kook. It was interesting to see how affirmation of certain classical views of hierarchy in Jewish/gentile relations existed alongside full acceptance of the other, in his or her concrete reality. He never really resolved the ambivalence in halachic tradition toward Christianity. At various point the tension between halachic precedents played out in his own soul or in his own personal decision making. Yet, this had absolutely no impact on the depth of his presence and friendship with top Christian clergy.

The point is not just that he met with the Pope (and donned a white kippah to match that of the Pope). It is not that he was simply important, or a good conversation partner or reference point. It is, rather, that he approached all these relationships with a kind of presence and open-heart that cut across religious differences and even the opinions he himself held, or struggled with, that might have been obstacles to such friendship.

As I think of it, his personal testimony is all the more remarkable, in view of how classical, or conservative, he was in his theological views. Where did the spirit of openness, the spirit of Elijah, if you will, come from, if it was not a consequence of views, opinions and halachic positions? I once posed that question to him, though not in the framework of such a paradox, but simply in amazement of the existential openness that characterized him. Where did you get it from? I asked. Well, he replied, look at where I grew up.

He intended to reference the open-minded home of his father, Rabbi David Hacohen, whose theological and philosophical works were a synthesis of Judaism and all aspects of broader philosophical knowledge. Or maybe he referenced the spirituality of his paternal home that would condition a heart such as his. And maybe there is a third dimension to his answer, one that comes to light in the amazing fact of him, the last person who knew Rav Kook in his lifetime, passing away on the yahrzeit of Rav Kook and being buried in proximity to him.

Perhaps he really grew up in the shadow of Rav Kook in ways that manifested through his relationships with other faiths. Rav Kook had a nearly unprecedented capacity for love, across all divides. Yet, at times he expressed positions that have led others to rejection and distance toward others. There is something, then, in the primacy of heart and being, that rises above opinions, views and positions. The last witness of Rav Kook seems to have imbibed that spirit of priestly love from the great master.

—————

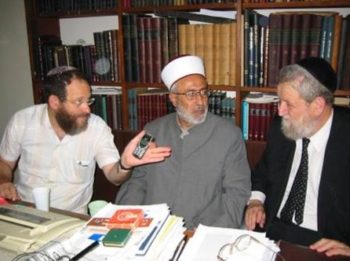

3. Judaism and Eastern Religions — Diplomatic Success and Theological Challenges

The Israeli Foreign Ministry, together with the American Jewish Committee and the Council of World Religious Leaders, hosted a high-level delegation of leaders from Eastern Religions. The head of the Sikh faith was there. Alon Goshen-Gottstein draws lessons from his participation at this high-level meeting, and reflects on the theological challenges of interfaith dialogue

So were high-level Hindu, Buddhist and Tao leaders from India and China as well as Shinto and Zoroastrian leaders. They were received with great honor by the President of Israel. Our Prime Minister made time on his busy schedule to receive them and urged that such meetings should become an annual event. The coming of such a high-level delegation to Israel was clearly an event, and a successful one, from the perspective of the diplomats who organized it. Israel has deepened its ties with Asia, through religious channels. Because most of these leaders have influence not only on millions of faithful but also on their governments, this is a significant political achievement.

President Rivlin with Hindu and Buddhist monks from delegation of Asian Religious Leaders

Woody Allen once quipped: Showing up is 80 percent of life. The fact that the meeting happened and garnered the high-level official attention it did is itself success, regardless of its contents. But if we are to make good on Mr. Netanyahu’s vision of an ongoing exchange, issues of substance must come to the forefront. As a consultant to the meeting in its planning stages and as one who contributed to the proceedings, I would raise three questions, relating to Judaism’s relations to Eastern faiths (faiths of Asia, as they were referred to in the recent meeting).

1. Whom do we talk to?

For diplomatic purposes, it is fine to lump all “Asian” religions into a bundle and bring the heads of the different religions to meet with the leaders of our state. From a religious perspective, it makes less sense. Judaism’s conversation with Shinto faith is nothing like its conversation with Sikh faith. Shinto believes, if I got it right, in 30,000 gods. It is also very tolerant, adaptable and could conform itself easily to modernity, as well as to various religious groups. If Japanese pacifism and peace-making are related to a particular theology, then a Jewish encounter with Shinto requires reflection on monotheism and its discontents or on what lessons can be carried over from Shinto into a Jewish framework. Sikhs, on the other hand, are monotheists, who integrate a military ethos with very refined spirituality. This raises an entirely different set of concerns for a meaningful conversation. Lumping all religions together pushes the conversation to the broadest common denominators – protection of planet, peacemaking, values in society. But holding conversations on these broad values without engaging the particular theologies of the traditions only affirms the starting point – the 80 percent of showing up. It affirms that somehow there are some values we would all like to see implemented in today’s world. But it does little to advance how Judaism, and the State of Israel, can learn from others, teach others, or collaborate with others in ways that are more than purely declarative or ceremonial.

2. What can we talk about and what do we ignore?

Rabbi Michael Melchior made an important presentation on religion and peacemaking. The Oslo peace process failed, he suggested, because it did not take into account identity. People will die for their identity and religious identity is an essential component of identity. The quest for affirming identity has been an important driver in the official Jewish-Hindu dialogue, launched in 2007, by Swami Dayananda (Click here to learn more). Dayananda was concerned about Christian missionary efforts against Hindus and sought to create an alliance with Judaism, whereby both non-missionary religions could stand up against missionary efforts. (As participants in the recent meeting joked: Between Israel, India and China we would number 2.5 billion people). Yet, a review of the proceedings of official Hindu-Jewish dialogue, surveyed in my The Jewish Encounter with Hinduism (Palgrave, 2016), shows that Jewish leaders have failed to raise their own identitarian issues in dialogue with others. While Hindus voiced their concerns regarding missionary activities, Jews remained silent on the reality of Israelis drawn to the ashrams of the very same leaders. The sight of an orange-clad Israeli swami, ordained by Swami Dayananda, at last week’s memorial lecture for Dayananda, brought home to me the challenge of not avoiding discussion of identity issues, as these concern Jewish participants in the dialogue.

Swami Dayananda

A second issue that was kept off the table and that must feature more prominently in a future conversation, and which indeed did feature in previous Hindu-Jewish summits, is the nature of belief in God, and in particular the challenge of idolatry. Is theological common-ground necessary for practical collaboration? Perhaps not. But it is necessary for successful transfer of ideas and inspiration across traditions.

The delegates presented both the President and the Prime Minister with the well-known image of Dancing Siva, one of the most iconic images of Hinduism. The gesture was obviously well-intended. Still, one is left wondering what have Hindu partners to the dialogue with Jewish religious officials learned about Judaism, or rather: what have they not learned? Good interfaith dialogue should sensitize us to the reality of the other, to his concerns and to differences in worldview. It seems that the dialogue has not yet reached a point of sufficient honesty, trust, breadth or representativity (some or all of the above) to allow Jewish participants to voice their concerns, in a spirit of dialogue and understanding. Or perhaps the dialogue has not yet created the mechanisms of sharing, consultation and collaboration that would lead to deeper understanding of each side’s particular sensitivities.

Meeting with Israeli President Reuven Rivlin

3. Whom do we engage in conversation?

In 2007 and 2008 the Israeli Foreign Ministry was able to engage the two Chief Rabbis of Israel, Rabbis Metzger and Amar, in the dialogue with Hindu leaders. The recent event was marked by the absence of high-level Jewish religious leaders. The Chief Rabbinate’s representatives to the dialogue (Rabbis David Rosen and Daniel Sperber) were in attendance. So were many other rabbis who have a voice in the community, such as Rabbis Yuval Cherlow, Avi Giesser and Michael Melchior. But the discrepancy was obvious. The individuals who would be seen as the counterparts to the visiting Asian religious leaders were absent from the table. Their place was filled by State and diplomatic heads. This says something about the present state of the Chief Rabbinate and of official Judaism. It also points to the work ahead. Meaningful conversation must engage the highest ranking representatives and ultimately filter down to religious communities – of Jews and of leaders of other religions.

The dialogue with Asian religious leaders was an important and encouraging first step. That it happened is half the success, nay: 80% of the success. But the remaining 20% may be the hardest. If the dialogue is to bear long-term fruit, and if it is to become an ongoing event, the significant diplomatic success must be “converted” to the beginnings of a meaningful conversation that will not only delight in the very fact that a conversation is taking place, but also engage the challenging and meaningful religious issues that are appropriate to each of the religions and Judaism’s conversation with it.

* All pictures courtesy of Israeli Foreign Ministry

—————

4. Sharing Wisdom

The Sharing Wisdom section of our newsletter is comprised of the wisdom of Rabbi Shear Yashuv Cohen.

On Leadership:

To be an effective spiritual leader in this generation the rabbi must possess three qualities: the ability to enlighten and to make oneself heard and warmth of spirit.”

June 1975, the year Rabbi Cohen was appointed Chief Rabbi of Haifa

On Jewish-Christian relationships:

“There is a long, hard and painful history of the relationship between our people, our faith, and the Catholic Church leadership and followers — a history of blood and tears, I deeply feel that my standing here before you is very meaningful. (…) It brings with it a signal of hope and a message of love, co-existence, and peace for our generation, and for generations to come.”

Addressing the Synod of Bishops, Rome, October 6, 2015

On Sacred Texts:

“We pray God using his own words, as related to us in the Scriptures. Likewise, we praise him — also using his own words from the Bible. (…) We ask for his mercy — mentioning what he has promised to our ancestors and to us. (…) Our point of departure stems from the treasures of our religious tradition, even while we endeavor to speak in a modern and contemporary language and address present issues.” Cohen said: “It is amazing to observe how the Holy Scriptures never lose their vitality and relevance to present issues of our time and age. This is the miracle of the everlasting and perpetual word of God.”

Explaining the role of Scripture in the Jewish faith, October 6, 2015